Island Stories:

![]() Danzig

Mine

Danzig

Mine

![]() Zeballos

Iron Mine

Zeballos

Iron Mine

![]() Conuma

Peak 1910

Conuma

Peak 1910

Alexandra Peak

Argus Mountain

Bate/Alava Sanctuary

Beaufort Range

Big Interior Mtn

Big Interior Mtn 1913

Part 1

Part 2

Bolton Expedition 1896

Cliffe Glacier

Clinton Wood

Comox Glacier

Comox Glacier 1922

Comox Glacier 1925

Comstock Mtn

Conuma Peak

Copper King Mine

Crown Mtn

Elkhorn 1912

Elkhorn 1949

Elkhorn 1968

Eugene Croteau

Golden Bullets

Golden Hinde 1913/14

Golden Hinde 1937

Golden Hinde 1983

Harry Winstone Tragedy

Jack Mitchell

Jim Mitchell Tragedy

John Buttle

Judges Route

Koksilah's Silver Mine

Landslide Lake

Mackenzie Range

Malaspina Peak

Mariner Mtn

Marjories Load

Matchlee Mountain

Mount McQuillan

Mt. Albert Edward

Mt. Albert Edward 1927

Mt. Albert Edward 1938

Mt. Becher

Mt. Benson 1913

Mt. Benson

Mt. Doogie Dowler

Mt. Colonel Foster

Mt. Hayes/Thistle Claim

Mt. Maxwell

Mt. Sicker

Mt. Tzouhalem

Mt. Whymper

Muqin/Brooks Peninsula

Nine Peaks

Queneesh

Ralph Rosseau 1947

Rosseau Chalet

Ralph Rosseau Tragedy

Rambler Peak

Red Pillar

Rex Gibson Tragedy

Sid's Cabin

Steamboat Mtn

Strathcona Park 1980's

The Misthorns

The Unwild Side

Victoria Peak

Waterloo Mountain 1865

Wheaton Hut/Marble Meadows

William DeVoe

Woss Lake

You Creek Mine

Zeballos Peak

Other Stories:

Sierra

de los Tuxtlas

Antarctica

Cerro del Tepozteco

Citlaltepetl

Huascaran

Mt. Roraima

Nevada Alpamayo

Nevada del Tolima

Nevado de Toluca

Pico Bolivar

Popocatepetl

Uluru/Ayers Rock

Volcan Purace

Volcan San Jose

Biographies

Island 6000

Cartoons

Order the Book

Contact Me

Links

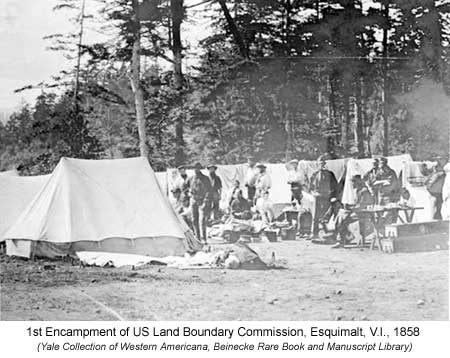

The John Buttle Story

by Lindsay

Elms

Of all the beautiful lakes on Vancouver Island, one of the most spectacular is Buttle Lake. Named after the explorer John Buttle, this lake is 32 kilometres long and is found nestled within the confines of Strathcona Provincial Park. This was the first provincial park in British Columbia and was established on March 1, 1911, by the Premier Sir Richard McBride.

Born

in England, John James Taylor Buttle (1838 - 1908) came to the Crown Colony

of Vancouver Island on the Steamer Parana in 1858 with a party

of Royal Engineers headed by Colonel John Summerfield-Hawkins. Corporal

Buttle had undertaken a course of instructions from the prestigious Kew

Gardens in England and upon arriving in North America worked as an Assistant

Botanical Collector for the Oregon Boundary Commission from the spring

of 1858 to the spring of 1862. In 1863 he worked on the proposed route

from Bute Inlet, up the Homathco River and into the Cariboo gold-fields

for Alfred Waddington

and then in 1864 John Buttle became a member of the first Vancouver Island

Exploring Expedition that explored the west coast and southern regions

of the island.

Born

in England, John James Taylor Buttle (1838 - 1908) came to the Crown Colony

of Vancouver Island on the Steamer Parana in 1858 with a party

of Royal Engineers headed by Colonel John Summerfield-Hawkins. Corporal

Buttle had undertaken a course of instructions from the prestigious Kew

Gardens in England and upon arriving in North America worked as an Assistant

Botanical Collector for the Oregon Boundary Commission from the spring

of 1858 to the spring of 1862. In 1863 he worked on the proposed route

from Bute Inlet, up the Homathco River and into the Cariboo gold-fields

for Alfred Waddington

and then in 1864 John Buttle became a member of the first Vancouver Island

Exploring Expedition that explored the west coast and southern regions

of the island.

In 1861 the Pre-emption Proclamation had stimulated agricultural settlement at Cowichan and Comox, since by this procedure settlers might take up unsurveyed land prior to arranging payment to the government. In 1863, Governor James Douglas, in an address to the Colonial Legislature, spoke of "the great importance of providing a Geological Survey of the Colony." The government was interested in knowing just how much land was available as the amount of land either sold or pre-empted in 1862 was almost double that in 1861. The discovery of gold in the Fraser Valley in 1858 and the Cariboo in 1863, had also sparked interest in the possibility of there being gold on the island.

These were sufficient reasons for launching an exploring expedition in the mid-1860's, but what was required was an official sponsor and this arrived when Arthur Edward Kennedy became governor in March 1864. Upon visiting the gold diggings at Goldstream near Victoria, Kennedy pledged official support for an expedition by a government contribution of two dollars for every dollar contributed by the general public. A committee was formed by some of Victoria's leading citizens to organize an expedition and to arouse interest and financial support the committee then arranged a public meeting.

Vying for the opportunity to command the expedition, were two scientists newly arrived to the West Coast. Dr. Robert Brown , a young twenty-two year old Scotsman, arrived on Vancouver Island in 1863 for the purpose of collecting seeds, roots and plants for the Botanical Association of Edinburgh. Brown wasn't satisfied with being a mere 'seed collector' as he was a trained botanist, so he applied to command the expedition. The other scientist, Dr. David Walker, was a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in Dublin. Walker had also arrived in Victoria in 1863 following an expedition in search of Sir John Franklin in the high Arctic, and upon hearing of the proposed expedition, applied to be its leader. However, on June 1 1864, the committee appointed Brown as the commander of the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition (VIEE).

That summer was very successful for Robert Brown and the VIEE but unfortunately it was due to his contract with the Botanical Association that led him to relinquish the command of the second Exploring Expedition in 1865. He suggested that the leadership be handed over to John Buttle.

The committee accepted Brown's recommendation that Buttle become the new commander and Buttle's first job was to select a base for a more ambitious expedition to explore the west coast. After a seventeen day reconnaissance, Buttle recommended that the main exploration should begin at Clayoquot Sound approximately where Robert Brown's party had finished the year before and should continue to Nimpkish via Nootka Sound and the Tahsis Inlet.

Speed was essential as the summer was fast approaching and the party had to be organized. Supplies were accumulated and the other members were chosen, seven in total including Buttle. The party comprised of Thomas Forgie, a Royal Engineer like Buttle who worked on the North American Boundary Commission until his discharge in 1862 and then as a miner on the Columbia gold-fields for two years, Magin Hancock, an ex-Cariboo miner, Francis McCausland, an old Australian miner, Thomas Laughton, an interpreter, and two native guides, Tomo Antonie and Timothy O'Brien. It was obvious by the men's occupations that there was a strong tendency towards mineral exploration, but all these men were well versed in the outdoors and were capable of carrying out the exploration of the area that was required of them.

On June 19, the Navy's H.M.S. Forward, left Esquimalt and landed Buttle's party in Clayoquot Sound two days later, where they commenced to set up a base camp before proceeding to explore the surrounding area. For the next five weeks Buttle and his men explored the various arms and inlets of Clayoquot Sound until on July 28 they arrived at a point two miles up the Bear (Bedwell) River. At this point the Bear River forked and the party split into two. Buttle, with McCausland, Antoine and two other natives who joined the expedition from Oinimitis, the native village at the mouth of the Bear River, explored the right branch (now called the Ursus River), while Hancock and the rest proceeded up the left branch (Bedwell River). Both parties took with them ten days' provisions and started out on the morning of July 29 on their respective journeys.

Buttle sent periodic reports to the Daily British Colonist newspaper in Victoria and on August 12, 1865, they printed:

… I ascended one of the mountains arising from our camp, accompanied by Tomo and the two Indians. At about 4000 feet we came to snow; this continued in various depths till we arrived at the summit, an altitude of about 6000 feet above the level of the sea. From the summit I got a good view in the direction of Comox; and in what I should judge to be the centre of the Island, I saw a very large body of water - I should suppose twenty miles long. It is either a chain of lakes, or else one very large lake with islands in it.

From Buttle's personal diary of the trip dated August 2, he wrote: "…more in the centere (sic) of the Island I saw a beautiful sheet of water at the very least twenty miles long it appears to be a chain of lakes averageing (sic) about two miles in width and surrounded by low hills …"

After ascending the mountain Buttle returned to camp believing he had discovered a large body of water previously unseen. Upon reuniting with Magin Hancock and his party, who claimed to have found gold in payable quantities up the left fork, the party continued with the exploration of the west coast arriving at Nootka Sound and then travelling as far as Conuma (Woss) Lake via Tahsis Inlet. Buttle was hoping to get to Nimpkish, but illness and bad weather forced him to turn back to Victoria. There John Buttle and his party had to deal with angry prospectors who had rushed to the Bear River upon hearing of gold, only to be disillusioned by the quantities. The miners complained long and loud saying Hancock and Forgie were "irresponsible", and Buttle "wasn't fit to command the cook's galley". They believed they had been hoaxed and the government was to blame for allowing the reports to be published.

Criticized for the Bear River fiasco, Buttle moved on to California and was rarely heard of again on Vancouver Island.

It was twenty-seven years before any European was to again see the lake Buttle believed he saw. In 1892 the B.C. Government employed William Ralph to survey the western boundary of the Esquimalt and Nanaimo (E & N) Railway Company Land Grant from Otter Point near Sooke to the foot of Crown Mountain. Ralph travelled in a straight line taking bearings as he went. On June 25, 1892, Ralph wrote:

At 117.5 miles, height 7,000 feet, Buttle's Lake is visible ahead. We now descend very steep to Buttle's Lake at 123 mile, height 800 feet. Buttle's Lake is 18 miles long and from 20 to 30 chains wide; it runs nearly north and south, is surrounded by high mountains, and its outlet is Campbell River.

William Ralph was able to confirm that indeed there was a large lake and that in all probability it was the lake John Buttle had seen. Four years later the exploring rector William Bolton visited Buttle's Lake while on his north/south traverse of Vancouver Island. Bolton wrote in his dairy on August 5, 1896:

It is, so far as the writer's knowledge extends, the peer of all the Islands lakes in its scenic beauty. Banked on both sides by high mountains, snowcapped and rugged.

There is no doubt that Buttle Lake is the jewel of Strathcona Park and its name is befitting of the early explorer but the question must be asked, 'Did John Buttle really see the lake that now bears his name?'

Over the years a number of people who have spent many of their free summer days exploring Strathcona Park have questioned Buttle's account and sighting of the large body of water. They have just said Buttle's sense of direction seems slightly in error, but it is probable that the body of water he saw was indeed Buttle's Lake. It was never questioned any further. From Buttle's report to the newspaper we have to wonder why he said it was: "…either a chain of lakes or one very large lake with islands in it," and yet in his diary: "…it appears to be a chain of lakes," not one big lake. Was there some doubt in his mind when it came to writing his report. Maybe this was brought about by the weather not being clear on the summit day; perhaps there was an inversion in the weather happening. An inversion is a common occurrence on the island and is when a thick cloud layer lingers in the valley bottoms but above, on the mountain tops, it is clear. As the day draws on this cloud layer will usually start to break up and eventually disperse. Maybe while Buttle was on the summit of the mountain the clouds were beginning to disperse below and he could see the occasional glimmer of water and assumed that there was a large body of water below.

From Buttle's map we are able to identify which summit he was standing on, and as mountaineers we know that it is impossible to see Buttle Lake from this point. The Buttle Lake is still twenty kilometres away to the north as the crow flies. There are mountains in between that are taller by 400 metres (1,300 feet) such as Big Interior Mountain and Nine Peaks and we also know that even from these summits you can't see Buttle Lake. The only lakes that can be seen from where Buttle was are Leader Lake at the head of McBride Creek which was just slightly to the north of east, McBride Lake and Great Central Lake which McBride Creek drains into eight kilometres from Leader Lake. The other lake that Buttle could see would be Sproat Lake in the distance. At the head of the Ursus River, not far from where Buttle stood, is a pass and on the other side of that is the Taylor River. The Taylor River flows into Sproat Lake and it is possible that Buttle mistook this as Great Central Lake as it is a long similar looking lake.

Buttle also mentions that the lake/lakes appear to be surrounded by low hills. The mountains surrounding Buttle Lake are anything but low as Ralph's account states that it is surrounded by high mountains up to 7,000 feet. It would be more reasonable to assume that it was Leader, McBride and Great Central Lakes that John Buttle saw from the top of the mountain. With clouds down in the valley it is plausible to think that this could be one large lake or a chain of lakes, which it in fact is.

No matter what, we are only speculating but nowadays on our side we do have accurate maps available and better knowledge of the area in question. Whether John Buttle ever saw the lake that bears his name we shall never know for certain but it is a fitting name for one of the most beautiful lakes on Vancouver Island.

How to order | | About the Author || Links || Home

Contact:

Copyright ©

Lindsay Elms 2001. All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.beyondnootka.com

http://www.lindsayelms.ca