Island Stories:

![]() Danzig

Mine

Danzig

Mine

![]() Zeballos

Iron Mine

Zeballos

Iron Mine

![]() Conuma

Peak 1910

Conuma

Peak 1910

Alexandra Peak

Argus Mountain

Bate/Alava Sanctuary

Beaufort Range

Big Interior Mtn

Big Interior Mtn 1913

Part 1

Part 2

Bolton Expedition 1896

Cliffe Glacier

Clinton Wood

Comox Glacier

Comox Glacier 1922

Comox Glacier 1925

Comstock Mtn

Conuma Peak

Copper King Mine

Crown Mtn

Elkhorn 1912

Elkhorn 1949

Elkhorn 1968

Eugene Croteau

Golden Bullets

Golden Hinde 1913/14

Golden Hinde 1937

Golden Hinde 1983

Harry Winstone Tragedy

Jack Mitchell

Jim Mitchell Tragedy

John Buttle

Judges Route

Koksilah's Silver Mine

Landslide Lake

Mackenzie Range

Malaspina Peak

Mariner Mtn

Marjories Load

Matchlee Mountain

Mount McQuillan

Mt. Albert Edward

Mt. Albert Edward 1927

Mt. Albert Edward 1938

Mt. Becher

Mt. Benson 1913

Mt. Benson

Mt. Doogie Dowler

Mt. Colonel Foster

Mt. Hayes/Thistle Claim

Mt. Maxwell

Mt. Sicker

Mt. Tzouhalem

Mt. Whymper

Muqin/Brooks Peninsula

Nine Peaks

Queneesh

Ralph Rosseau 1947

Rosseau Chalet

Ralph Rosseau Tragedy

Rambler Peak

Red Pillar

Rex Gibson Tragedy

Sid's Cabin

Steamboat Mtn

Strathcona Park 1980's

The Misthorns

The Unwild Side

Victoria Peak

Waterloo Mountain 1865

Wheaton Hut/Marble Meadows

William DeVoe

Woss Lake

You Creek Mine

Zeballos Peak

Other Stories:

Sierra

de los Tuxtlas

Antarctica

Cerro del Tepozteco

Citlaltepetl

Huascaran

Mt. Roraima

Nevada Alpamayo

Nevada del Tolima

Nevado de Toluca

Pico Bolivar

Popocatepetl

Uluru/Ayers Rock

Volcan Purace

Volcan San Jose

Biographies

Island 6000

Cartoons

Order the Book

Contact Me

Links

Colombia: land of Juan Valdez coffee, brilliant green emeralds and the most sought after cocaine in the world, however, the country has more to offer for the adventurer who is not easily intimidated by machinegun-toting federal police and narco-terrorists. The mountains are a mecca for climbers although they do begin to taper off slightly in height when compared to the rest of South America. Nevertheless, the highest mountains in Colombia rise to 5,700 metres and are located in the north of the country in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, while to the east bordering with Venezuela is the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy with peaks rising to over 5,300 metres. From the south at the border with Ecuador through to the central region of Colombia are some of the world's most active volcanoes: Volcán Galeras, Volcán Puracé, Volcán Machin and Volcán Sotará. These volcanoes form part of the eastern edge of the "Pacific Ring of Fire."

However,

in a cluster located to the southwest of Bogota and known as Parque Nacional

Los Nevados is a chain of volcanoes that are probably the most popular

climbing area in Colombia as well as a popular ski spot in winter. At

the northern end of this park is Nevado del Ruiz (5,389m) the highest

most active volcano in Colombia, while at the southern end is Nevada del

Tolima (5,215m.) Located between them are two other volcanoes: Nevado

de Santa Isabel (4,930m) and Nevado Quindio (4,700m.) It is their relatively

easy road access that has drawn not only local climbers but mountaineers

from around the world and has made the traverse of all four peaks, which

takes about seven days to complete, a popular route.

However,

in a cluster located to the southwest of Bogota and known as Parque Nacional

Los Nevados is a chain of volcanoes that are probably the most popular

climbing area in Colombia as well as a popular ski spot in winter. At

the northern end of this park is Nevado del Ruiz (5,389m) the highest

most active volcano in Colombia, while at the southern end is Nevada del

Tolima (5,215m.) Located between them are two other volcanoes: Nevado

de Santa Isabel (4,930m) and Nevado Quindio (4,700m.) It is their relatively

easy road access that has drawn not only local climbers but mountaineers

from around the world and has made the traverse of all four peaks, which

takes about seven days to complete, a popular route.

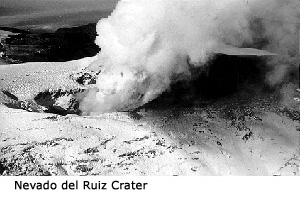

But it is not just the climbing that has made these mountains famous. On November 13, 1985, at 9:08 p.m. a catastrophic event took place that made headlines around the world when Nevado del Ruiz erupted. Within four hours of the beginning of the eruption, lahars had traveled one hundred kilometres and left behind a wake of destruction: more than 23,000 people were killed, about 5,000 injured, and more than 5,000 homes destroyed along the Chinchiná, Gualí, and Lagunillas Rivers. Hardest hit was the town of Armero at the mouth of the Río Lagunillas canyon. Three quarters of its 28,700 inhabitants perished.

Earlier

eruptions of Nevado del Ruiz occurred in 1595 and again in 1845 and it

is known the eruptions melted snow and ice and produced mudflows that

travelled many kilometres from the volcano. These mudflows were confined

to the valleys that drain the volcano and caused no deaths. However, beginning

in November 1984, Nevado del Ruiz began showing clear signs of unrest

again, including earthquakes, increased fumarolic activity from the summit

crater, and small phreatic (steam) explosions. Scientists watched the

mountain for the next year but were unable to predict the eruption that

sent a series of pyroclastic flows and surges across the volcanoes broad

ice-covered summit. Within minutes, pumice and ash began to fall to the

northeast along with heavy rain that had started earlier in the day. The

crater was enlarged slightly by the eruption, and the summit area was

quickly covered with layers of pyroclastic flow deposits as thick as eight

metres.

Earlier

eruptions of Nevado del Ruiz occurred in 1595 and again in 1845 and it

is known the eruptions melted snow and ice and produced mudflows that

travelled many kilometres from the volcano. These mudflows were confined

to the valleys that drain the volcano and caused no deaths. However, beginning

in November 1984, Nevado del Ruiz began showing clear signs of unrest

again, including earthquakes, increased fumarolic activity from the summit

crater, and small phreatic (steam) explosions. Scientists watched the

mountain for the next year but were unable to predict the eruption that

sent a series of pyroclastic flows and surges across the volcanoes broad

ice-covered summit. Within minutes, pumice and ash began to fall to the

northeast along with heavy rain that had started earlier in the day. The

crater was enlarged slightly by the eruption, and the summit area was

quickly covered with layers of pyroclastic flow deposits as thick as eight

metres.

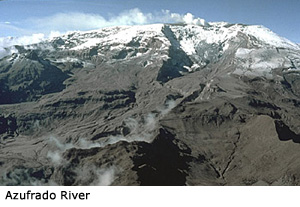

Hot

rock fragments of the pyroclastic flows and surges quickly eroded and

mixed with Ruiz's snow and ice, melting about ten percent of the volcanoes

ice cover. In places, channels one hundred metres wide and two to four

metres deep were eroded into the icecap. Flowing mixtures of water, ice,

pumice and other rock debris then descended several thousand metres from

the summit and sides of the volcano as a series of small lahars into the

six major river valleys draining the volcano. In one river, the Azufrado,

scientists found a piece of ice two metres across about three kilometres

from the crater.

Hot

rock fragments of the pyroclastic flows and surges quickly eroded and

mixed with Ruiz's snow and ice, melting about ten percent of the volcanoes

ice cover. In places, channels one hundred metres wide and two to four

metres deep were eroded into the icecap. Flowing mixtures of water, ice,

pumice and other rock debris then descended several thousand metres from

the summit and sides of the volcano as a series of small lahars into the

six major river valleys draining the volcano. In one river, the Azufrado,

scientists found a piece of ice two metres across about three kilometres

from the crater.

In the Guali River valley lahars travelled down at an average speed of sixty kilometres per hour and some were as thick as fifty metres. By incorporating water and debris from along river channels, the lahars grew in size as they moved away from the volcano. Some lahars increased up to four times their initial volumes as they eroded soil, loose rock debris and stripped vegetation from the river channels. This eruption of Nevado del Ruiz was the second mostly deadly of the twentieth century (Mount Pelee in Martinique was first, killing 29,000 people in its 1902 eruption.) It is believed that one tenth of the world's population live within the danger zone of volcanoes.

When Geoff Mahan and I arrived in Ibaque in September, 1988 after having climbed Volcán Puracé a few days before we decided to climb one of the volcanoes in Los Nevados. My friend Mario La Rotta, who we were staying with, introduced us to Manolo Barrios, a local mountain guide, who was able to give directions on how to get to Nevado del Tolima (the closest mountain to Ibaque) and a route description. We spent the next day rock climbing at Chicoral under a blistering equatorial sun and then returned to Ibaque to organize what we would need for the climb.

Sunday morning (4th) we were up early and got a taxi down to Cooperativa Velotax where we could get a ride with the local milk truck (Lechera) to the end of the road at El Silencio. The crowded ride on the milk truck took two took hours as we passed through lush tropical jungle: the sound of exotic birds being drowned out by rattling milk crates.

From

El Silencio we had a two kilometre walk to the hot springs at El Rancho

where the climbing began. Initially the trail was steep and muddy as it

followed a creek bed but it gradually eased off as we got near La Cascada

(The Waterfall) at around 3,000 metres. At this point we entered the mist

and were unable to see anything until we arrived at La Cueva (The Cave)

at 3,720 metres, four hours after leaving El Rancho. Here we found a rather

dilapidated hut perched under an overhang beside a small waterfall. That

afternoon we sat outside soaking up the sun as it periodically broke though

the mist. Occasionally we got a view of the route towards the summit and

it looked a long way. That night the noise of the waterfall nearby sounded

like a torrential downpour outside and I pulled the hood on my sleeping

bag tighter around my head to dampen the roar.

From

El Silencio we had a two kilometre walk to the hot springs at El Rancho

where the climbing began. Initially the trail was steep and muddy as it

followed a creek bed but it gradually eased off as we got near La Cascada

(The Waterfall) at around 3,000 metres. At this point we entered the mist

and were unable to see anything until we arrived at La Cueva (The Cave)

at 3,720 metres, four hours after leaving El Rancho. Here we found a rather

dilapidated hut perched under an overhang beside a small waterfall. That

afternoon we sat outside soaking up the sun as it periodically broke though

the mist. Occasionally we got a view of the route towards the summit and

it looked a long way. That night the noise of the waterfall nearby sounded

like a torrential downpour outside and I pulled the hood on my sleeping

bag tighter around my head to dampen the roar.

The next morning my alarm went off at 3:20 A.M., however, since the thick

fog still hadn't lifted we decided to curl up for another couple of hours.

We finally got up at 5:30 and were away by 6:15. For the next two and

a half hours we climbed through the Frailejon (Grey Friars) forest until

we hit the snowline just below the place called Latas. Here the hard work

began! Above us we could just pick out the black rocks of Cerro Negro

and La Canaleta (The Canal) that ascends to the right of Cerro Negro, however, we had to plough through

snow knee deep to thigh deep that was physically taxing and time consuming.

Conditions remained misty and only brief clearances showed us we were

getting close to Cerro Negro. Time ticked by as we took turns breaking

the trail while the crust layer on top of the snow punched into our shins

with every step. A pair of soccer shin splints would have been handy at

this point! At the top of La Canaleta we continued straight up to the

crater. Here we roped up as the lighting was flat and we were unable to

see any definition on the snow. We hadn't seen any crevasses but Manolo

had warned us that they were around. We circumvented the crater to the

left and moved over low angled snow slopes to the rounded summit of Nevada

del Tolima. It had taken us six hours from La Cueva to the summit and

three and a half of those hours were on the soft snow on the last seven

hundred metres. However, standing on the mist-shrouded summit still seemed

worth the effort.

that ascends to the right of Cerro Negro, however, we had to plough through

snow knee deep to thigh deep that was physically taxing and time consuming.

Conditions remained misty and only brief clearances showed us we were

getting close to Cerro Negro. Time ticked by as we took turns breaking

the trail while the crust layer on top of the snow punched into our shins

with every step. A pair of soccer shin splints would have been handy at

this point! At the top of La Canaleta we continued straight up to the

crater. Here we roped up as the lighting was flat and we were unable to

see any definition on the snow. We hadn't seen any crevasses but Manolo

had warned us that they were around. We circumvented the crater to the

left and moved over low angled snow slopes to the rounded summit of Nevada

del Tolima. It had taken us six hours from La Cueva to the summit and

three and a half of those hours were on the soft snow on the last seven

hundred metres. However, standing on the mist-shrouded summit still seemed

worth the effort.

After ten minutes we realised there was no point in hanging around too long on the summit as it was obvious the mist wasn't going to clear. The descent was just as tiring as the ascent and we were glad to finally get off the snow and onto solid terra firma. By 2:30 P.M. Geoff and I arrived exhausted back at the little hut and had a late lunch and then spent the rest of the afternoon relaxing.

That night I slept the sleep of the dead and felt fully refreshed the next morning when I woke up. Geoff and I left La Cueva at 6:10 A.M. and arrived down at El Rancho an hour and three quarters later, a little muddy and damp with sweat. We hiked briskly the two kilometres to El Silencio and then we had an hour and a half to dry our damp gear in the sun before getting a ride on the milk truck back to Ibaque. The return trip taking longer than the ride in as the truck had to stop and pick up milk from the local farmers along the way.

Back in Ibaque we looked over some of Manolo's slides of the Los Nevados volcanoes. We would love to have spent more time in these mountains and complete the traverse over the other summits to Nevado del Ruiz, unfortunately we were running out of time as we wanted to get to the Mexican volcanoes.

Since 1985 the Colombian volcanoes have been relatively quiet, however, global warming has affected the mountains as the glaciers have shrunk significantly due to a decrease in the annual snowfall. In a report called "Thawing of the Peaks" by the Director of the Colombian government Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies it has been announced that water reservoirs around the central mountains could be dramatically reduced in the next one hundred years as the amount of accumulated snow decreases and runoff is reduced. This will affect the lives of those living on the rich soil surrounding the volcanoes. This had become evident not only on the mountains of Colombia but around the world and is a growing problem.

The volcanoes of Nevado del Ruiz and Nevada del Tolima in Parque Nacional Los Nevados in central Colombia are beautiful mountains and should not be dismissed by climbers visiting South America. Yes, Colombia is a violent country if we listen to the news but the people are friendly and the scenery spectacular. I left Colombia with the knowledge that one day I would return and in a little café in a mountain village savour a revitalizing cup of Juan Valdez's coffee while experiencing the high of climbing another beautiful mountain.

How to order | | About the Author || Links || Home

Contact:

Copyright ©

Lindsay Elms 2001. All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.beyondnootka.com

http://www.lindsayelms.ca