Island Stories:

![]() Danzig

Mine

Danzig

Mine

![]() Zeballos

Iron Mine

Zeballos

Iron Mine

![]() Conuma

Peak 1910

Conuma

Peak 1910

Alexandra Peak

Argus Mountain

Bate/Alava Sanctuary

Beaufort Range

Big Interior Mtn

Big Interior Mtn 1913

Part 1

Part 2

Bolton Expedition 1896

Cliffe Glacier

Clinton Wood

Comox Glacier

Comox Glacier 1922

Comox Glacier 1925

Comstock Mtn

Conuma Peak

Copper King Mine

Crown Mtn

Elkhorn 1912

Elkhorn 1949

Elkhorn 1968

Eugene Croteau

Golden Bullets

Golden Hinde 1913/14

Golden Hinde 1937

Golden Hinde 1983

Harry Winstone Tragedy

Jack Mitchell

Jim Mitchell Tragedy

John Buttle

Judges Route

Koksilah's Silver Mine

Landslide Lake

Mackenzie Range

Malaspina Peak

Mariner Mtn

Marjories Load

Matchlee Mountain

Mount McQuillan

Mt. Albert Edward

Mt. Albert Edward 1927

Mt. Albert Edward 1938

Mt. Becher

Mt. Benson 1913

Mt. Benson

Mt. Doogie Dowler

Mt. Colonel Foster

Mt. Hayes/Thistle Claim

Mt. Maxwell

Mt. Sicker

Mt. Tzouhalem

Mt. Whymper

Muqin/Brooks Peninsula

Nine Peaks

Queneesh

Ralph Rosseau 1947

Rosseau Chalet

Ralph Rosseau Tragedy

Rambler Peak

Red Pillar

Rex Gibson Tragedy

Sid's Cabin

Steamboat Mtn

Strathcona Park 1980's

The Misthorns

The Unwild Side

Victoria Peak

Waterloo Mountain 1865

Wheaton Hut/Marble Meadows

William DeVoe

Woss Lake

You Creek Mine

Zeballos Peak

Other Stories:

Sierra

de los Tuxtlas

Antarctica

Cerro del Tepozteco

Citlaltepetl

Huascaran

Mt. Roraima

Nevada Alpamayo

Nevada del Tolima

Nevado de Toluca

Pico Bolivar

Popocatepetl

Uluru/Ayers Rock

Volcan Purace

Volcan San Jose

Biographies

Island 6000

Cartoons

Order the Book

Contact Me

Links

Woss

Lake:

And the Oolichan Trail

by Lindsay Elms

With

modern trail making equipment and park's trail standards, today's hikers

may find it difficult to relate to the hardships experienced by the early

explorers on Vancouver Island. These explorers didn't have topographical

maps that are in existence today and rarely were there trails to follow.

The few trails that did exist were ancient trading routes used seasonally

by the First Nation's People. These trails were not maintained and the

bush threatened to quickly reclaim any sign of passage. One of these trails

used by both native and the early explorers was the Oolichan Trail or

Grease Trail as it is some times called.

With

modern trail making equipment and park's trail standards, today's hikers

may find it difficult to relate to the hardships experienced by the early

explorers on Vancouver Island. These explorers didn't have topographical

maps that are in existence today and rarely were there trails to follow.

The few trails that did exist were ancient trading routes used seasonally

by the First Nation's People. These trails were not maintained and the

bush threatened to quickly reclaim any sign of passage. One of these trails

used by both native and the early explorers was the Oolichan Trail or

Grease Trail as it is some times called.

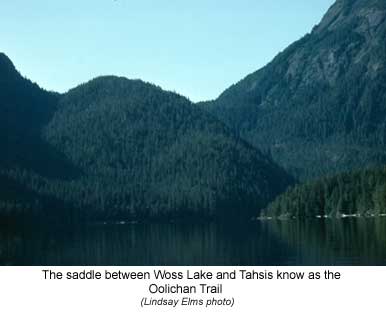

Beginning at the head of Woss Lake this trail crossed the divide to Tahsis Inlet on the West Coast. It was a trading route between the west and east coast First Nations of Vancouver Island. It received its name from the small silvery smelt like fish called the Oolichan (Thaleichthys Pacificus) that was found in the larger mainland rivers of British Columbia between March and May when they entered the rivers to spawn. This fish was sort after by the Indians because of its high oil content and unlike most fish oils, Oolichan is solid at ordinary temperatures.

For the east coast tribes the trail was easily reached by ascending the Nimpkish River to Nimpkish Lake and then continuing up the Woss River and onto Woss Lake. Although a journey of several days the route from the coast to the head of Woss Lake could be completed all the way by canoe. On the other side of the island the west coast tribes could paddle their canoes up the Tahsis Inlet and then a short distance up the Tahsis River to access the trail. The rest of the crossing being completed on foot.

It is because of the relatively low elevation of this pass, about five hundred metres, that made it a desirable trading route, but due to the area's high rainfall it has some of the thickest, most impenetrable bush on the island. Most other trails across the island require greater distances to be covered on foot and usually the passes are higher.

According to Franz Boas book Geographical Place Names of the Kwakiutl Indians, the word Woss comes from the Kwakwala language and it is spelled Wa's. The translation means "river on ground" and was a place near the Woss/Nimpkish river junction where the First Nation's People used to have a village site. Woss Lake is about twenty kilometres long and for most part is less than one kilometre wide.

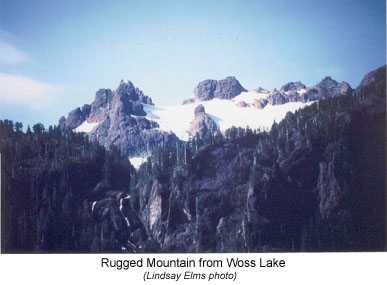

The first European to visit Woss Lake was Captain Hamilton Moffat, the officer-in-charge of the Hudson's Bay Company in Fort Rupert (near present day Port Hardy). Moffat left the Fort on July 1, 1852, and proceeded down the coast to the Nimpkish River. With six Indians he headed up the Nimpkish River to Nimpkish Lake and then reached Woss Lake, or Kanus Lake as he reported it, on July 4. On the morning of the 5th, accompanied by an Indian, Moffat attempted to ascend the jagged mountain to the west, which he called Ben Lomond. This was the first known attempt to climb what is today called by the more descriptive name 'Rugged Mountain.' The mountain's steep bluffs soon repulsed their advances and they descended, continuing with their journey across the Oolichan Trail to Tahsis Inlet. Because of its remote location it was not until thirteen years later in 1865 that another white man visited the lake.

On the 10th of September of that year, John Buttle and his Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition crossed the divide from the Tahsis Inlet and arrived at the southern end of what Buttle called Conuma Lake (now Woss Lake). They were accompanied by an Indian from the Clayoquot area and Tomo Antoine, an Iroquois Indian who guided numerous explorers on Southern Vancouver Island. Buttle's party were all seasoned prospectors as one of the main purposes of the expedition was to look for gold. British Columbia was hoping to stimulate its economy by finding another gold rush like those of the Fraser River and Cariboo.

The path they followed was the Oolichan Trail, which hadn't been travelled for several years and was overgrown with bushes through lack of use. The weather was miserable for the crossing as it had been raining continuously for the last two weeks and Buttle himself was suffering from an illness. He described the route across as: "very bad and … in places highly dangerous." Many of the logs used for bridges were rotten which further hindered their crossing. Although they searched they could find no traces of gold, however, veins of copper were found on their way up to the pass.

For the next five days, at their campsite on the lake, they worked on building a canoe and during that time the rain never let up. Finally Tomo and the Clayoquot Indian that Buttle had brought to act as guides, refused to continue any further on account of the conditions. The rivers descent from Conuma Lake to the Nimpkish Valley would be so rough they feared drowning and returned to Nootka Sound. Buttle decided to go on without them but he had to wait six days before the weather became fair enough to launch the canoe. With a sail rigged from a blanket and rough hewn paddles, Buttle's party made their way to the northern end of the lake. A recently deserted Indian lodge was found and it was assumed it was a salmon fishing lodge as large numbers of the fish were ascending the river to the lake and all night long they could be heard jumping.

The next day, with time and provisions running low, they returned to the head of the lake prospecting several streams along the way. Again no gold was found but some indication of copper continued showing. That night they camped at a good size river opposite their earlier campsite. The Indians called this place Kleetsic or White River due to its high silt content giving it a thick milky colour. This silt comes from the glaciers above as it grinds over the granite rocks of the Haihte Range freeing miniscule mineral particles. Buttle believed that this river would offer payable gold if it could be prospected at low water levels but it later proved to be of no consequence.

Three years later a Hudson's Bay Company employee, Pym Nevin Compton, arrived at the White River at the head of Conuma (Woss) Lake and found a tree with Buttle's name carved into it. Compton had reached the lake from the east coast ascending the Nimpkish River from Fort Rupert.

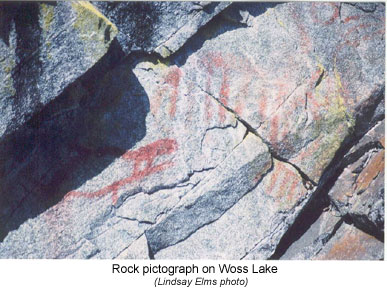

It was twenty-six years before any other Europeans visited the southern end of Woss Lake, however, others visited the northern end near where the forestry campground now stands. Across the lake from the campground Indian pictographs can still be found painted on the rocks just above the waterline; one of the few remaining signs of native passage.

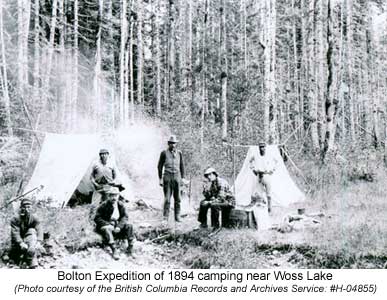

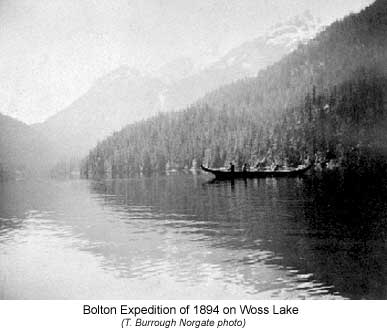

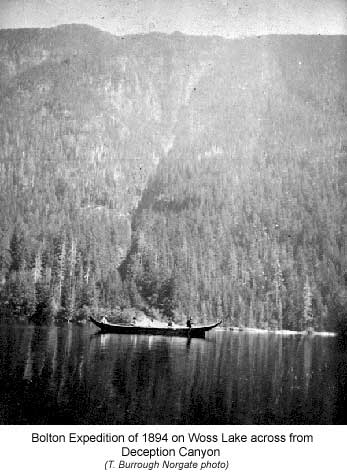

Reverend

William Bolton organized an ambitious expedition in 1894 to

traverse Vancouver Island from north to south travelling both by canoe

and on foot. On August 2, Bolton's support crew crossed the Oolichan Trail

from Tahsis to  Woss

Lake to wait for Bolton and his party with badly needed food supplies.

Bolton had fallen behind in his scheduledue to bad weather and never reached

his friends until the evening of the 10th. They entered the lake under

what Bolton said was "exquisite conditions." A cloudless blue

sky hovered above and the lake surface shimmered like a mirror in the

summer sun. Even the surrounding mountains stood out clear and crisp against

the sky. Bolton went on to exclaim in The Overland Monthly Vol

29:

Woss

Lake to wait for Bolton and his party with badly needed food supplies.

Bolton had fallen behind in his scheduledue to bad weather and never reached

his friends until the evening of the 10th. They entered the lake under

what Bolton said was "exquisite conditions." A cloudless blue

sky hovered above and the lake surface shimmered like a mirror in the

summer sun. Even the surrounding mountains stood out clear and crisp against

the sky. Bolton went on to exclaim in The Overland Monthly Vol

29:

There is so much beauty in this little spot that we were glad to spent the whole day here. Kowse Glacier on the summit of Rugged mountain is alone worth going many miles to see and then added to it are the waterfalls, which seem coming down everywhere, joining at the base into the milk white stream that was altogether too cold to sip even under the midday boiling sun.

The next day the party shouldered their packs and began the ascent over the divide to Tahsis Inlet, in places pulling themselves hand over hand through the thick vegetation. From the summit they had a wonderful view of Woss Lake before commencing the descent.

Today

the crossing from Woss Lake to the Tahsis Inlet is just as arduous as

what the early explorers found it. The milky white stream coming down

from Rugged Mountain still blends with the crystal clear waters of Woss

Lake. Of the Oolichan Trail, all that is left are two ancient culturally

modified trees depicting human faces twenty metres from the lakeshore.

The significance of these two trees, one carving facing north and the

other facing south, has been long lost but it is believed that they marked

the boundary between the two tribal groups. Perhaps a special ceremony

was performed between the trees before one tribe moved into the next tribe's

territory. This is just another part of the intrigue of the Oolichan Trail.

Today

the crossing from Woss Lake to the Tahsis Inlet is just as arduous as

what the early explorers found it. The milky white stream coming down

from Rugged Mountain still blends with the crystal clear waters of Woss

Lake. Of the Oolichan Trail, all that is left are two ancient culturally

modified trees depicting human faces twenty metres from the lakeshore.

The significance of these two trees, one carving facing north and the

other facing south, has been long lost but it is believed that they marked

the boundary between the two tribal groups. Perhaps a special ceremony

was performed between the trees before one tribe moved into the next tribe's

territory. This is just another part of the intrigue of the Oolichan Trail.

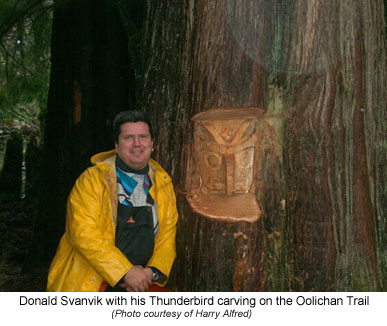

Recent trail development:

In 2001 the Namgis First Nation initiated a process to re-open and utilize

the Woss Lake-Tahsis Grease Trail. Over several gatherings by Namgis community

members at the head of Woss Lake, a preliminary trail was laid out, campsites

were designed and general archaeological investigations were completed.

In 2003-04 a preliminary business plan was written in partnership with

Ecotrust Canada for eco-tourism activities associated with the Grease

Trail, as well in 2004 the Namgis First Nation also benefited from funding

provided by British Columbia and Canada in a 'treaty related measure'

designed to improve Namgis capacity to research and protect archaeological

sites. In 2005, funding was secured from the Community Economic Adjustment

Fund, the North Vancouver Island Aboriginal Training Society and internal

Namgis sources to fully develop the Grease Trail. This work included the

installation of a composting toilet and shelter at the head of Woss Lake

as well as elevated tent platforms in the cedar grove, a tent platform

on the saddle at the height of land, and building of three kilometres

of trail. A band member, Donald Svanvik, carved a thunderbird into a cedar

tree at the start of the Grease Trail to signify the trade route on the

east side of the trail. He then carved another figure of a wolf part ways

up the trail to signify the west coast family ties that the Namgis have

with the Mowachaht First Nation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

How to order | | About the Author || Links || Home

Contact:

Copyright ©

Lindsay Elms 2001. All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.beyondnootka.com

http://www.lindsayelms.ca