Island Stories:

![]() Danzig

Mine

Danzig

Mine

![]() Zeballos

Iron Mine

Zeballos

Iron Mine

![]() Conuma

Peak 1910

Conuma

Peak 1910

Alexandra Peak

Argus Mountain

Bate/Alava Sanctuary

Beaufort Range

Big Interior Mtn

Big Interior Mtn 1913

Part 1

Part 2

Bolton Expedition 1896

Cliffe Glacier

Clinton Wood

Comox Glacier

Comox Glacier 1922

Comox Glacier 1925

Comstock Mtn

Conuma Peak

Copper King Mine

Crown Mtn

Elkhorn 1912

Elkhorn 1949

Elkhorn 1968

Eugene Croteau

Golden Bullets

Golden Hinde 1913/14

Golden Hinde 1937

Golden Hinde 1983

Harry Winstone Tragedy

Jack Mitchell

Jim Mitchell Tragedy

John Buttle

Judges Route

Koksilah's Silver Mine

Landslide Lake

Mackenzie Range

Malaspina Peak

Mariner Mtn

Marjories Load

Matchlee Mountain

Mount McQuillan

Mt. Albert Edward

Mt. Albert Edward 1927

Mt. Albert Edward 1938

Mt. Becher

Mt. Benson 1913

Mt. Benson

Mt. Doogie Dowler

Mt. Colonel Foster

Mt. Hayes/Thistle Claim

Mt. Maxwell

Mt. Sicker

Mt. Tzouhalem

Mt. Whymper

Muqin/Brooks Peninsula

Nine Peaks

Queneesh

Ralph Rosseau 1947

Rosseau Chalet

Ralph Rosseau Tragedy

Rambler Peak

Red Pillar

Rex Gibson Tragedy

Sid's Cabin

Steamboat Mtn

Strathcona Park 1980's

The Misthorns

The Unwild Side

Victoria Peak

Waterloo Mountain 1865

Wheaton Hut/Marble Meadows

William DeVoe

Woss Lake

You Creek Mine

Zeballos Peak

Other Stories:

Sierra

de los Tuxtlas

Antarctica

Cerro del Tepozteco

Citlaltepetl

Huascaran

Mt. Roraima

Nevada Alpamayo

Nevada del Tolima

Nevado de Toluca

Pico Bolivar

Popocatepetl

Uluru/Ayers Rock

Volcan Purace

Volcan San Jose

Biographies

Island 6000

Cartoons

Order the Book

Contact Me

Links

The Cliffe

Glacier:

And the Story of

the Surrounding Mountains

by Lindsay Elms

From

downtown Comox a large, steep sided mountain with a reddish tinge to the

rock and a flat top can be seen to the west of the Comox

Glacier, while to the northwest can be seen a mountain with

three summits, but what can't be seen is the large glacier that these

mountains rise above. This glacier is hidden by Queneesh:

the mythical name the First Nations People have given to the Comox Glacier.

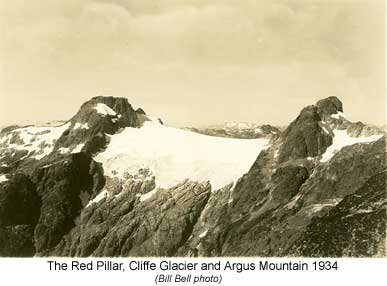

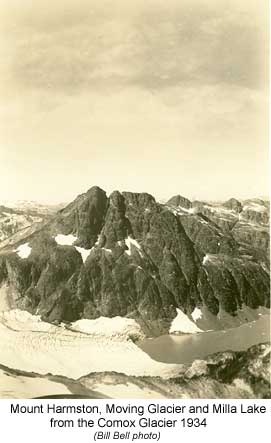

The second glacier was unnamed as were the two mountains until the early

1930's. The glacier became known as the Cliffe Glacier while the two mountains

became identified as The Red Pillar and Mount Harmston.

From

downtown Comox a large, steep sided mountain with a reddish tinge to the

rock and a flat top can be seen to the west of the Comox

Glacier, while to the northwest can be seen a mountain with

three summits, but what can't be seen is the large glacier that these

mountains rise above. This glacier is hidden by Queneesh:

the mythical name the First Nations People have given to the Comox Glacier.

The second glacier was unnamed as were the two mountains until the early

1930's. The glacier became known as the Cliffe Glacier while the two mountains

became identified as The Red Pillar and Mount Harmston.

Both the Cliffe Glacier and Mount Harmston are named after pioneering families in the Comox Valley. William and Florence Harmston arrived from England with their six-year-old daughter Florence, in 1862, as did the sixteen-year-old Samuel Cliffe. The Harmstons' settled in the valley while Cliffe initially ventured to Nanaimo, which was booming with the founding of rich coal seams. Cliffe eventually moved to Cumberland and in 1873 he married Florence Harmston.

In

1922 Harold Banks led the first trip from the Comox Valley to the Comox

Glacier (1922) that included in its party Alfred McNevin, James

Tremlett, and Reverend George Kinney. From the glacier they continued

north on to the Aureole Snowfield where they climbed Iceberg Peak and

Mount Celeste, and then descended down Shepherds Creek to Buttle Lake.

Although they saw the Cliffe Glacier from the Comox Glacier they never

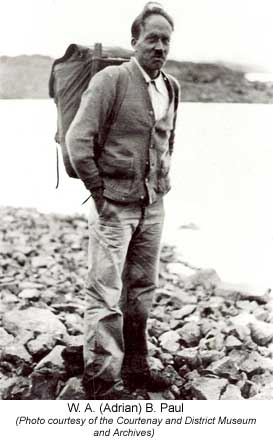

ventured on to it on this trip. It wasn't until August 1931, that W.A.B.

(Adrian) Paul of Comox, decided to led a trip to the virgin peak at the

southern end of the Cliffe Glacier that he believed was several hundred

feet high than "The Dome." Joining the party from Nanaimo was

Arthur Leighton, and from Courtenay Jack Gregson and Ben Hughes, the owner

of the Comox Argus newspaper.

In

1922 Harold Banks led the first trip from the Comox Valley to the Comox

Glacier (1922) that included in its party Alfred McNevin, James

Tremlett, and Reverend George Kinney. From the glacier they continued

north on to the Aureole Snowfield where they climbed Iceberg Peak and

Mount Celeste, and then descended down Shepherds Creek to Buttle Lake.

Although they saw the Cliffe Glacier from the Comox Glacier they never

ventured on to it on this trip. It wasn't until August 1931, that W.A.B.

(Adrian) Paul of Comox, decided to led a trip to the virgin peak at the

southern end of the Cliffe Glacier that he believed was several hundred

feet high than "The Dome." Joining the party from Nanaimo was

Arthur Leighton, and from Courtenay Jack Gregson and Ben Hughes, the owner

of the Comox Argus newspaper.

Ben Wallace Hughes was born in Croxall, Derbyshire, England in 1887 and was later educated in Strafford-on-Avon, at the grammar school Shakespeare once attended, a fact that may have inspired his love of writing. Hughes began an apprenticeship in electrical engineering but soon abandoned this for journalism. In 1903 Hughes and a friend traveled out to North America where he began work on a railway survey gang in New Mexico and then at the mines in Cobalt. He made a name for himself as a mining reporter and became the editor of Cobalt's Daily Nugget. He quit when asked to support the Conservative Party in the periodical as he advocated independent journalism. Hughes then went on to found the Northern Miner, which is now one of the largest mining newspapers in the world.

In 1916 he sold the Northern Miner and joined the army, serving overseas with the Royal Canadian Engineers until the end of the war. After the war he headed west to Vancouver Island and made his home in Comox. He bought the two year old Comox Argus and founded the West Coast Advocate in Port Alberni, and the short lived Parksville News, but eventually settled down to focus solely on the Argus. Hughes sold the Comox Argus in 1955 when he retired after thirty-six years as its publisher, but continued writing and published the History of the Comox Valley: 1862 to 1945. He founded the Courtenay and District Historical Society and served as secretary to the Chamber of Commerce. In 1970, at the age of eighty-seven, Ben Hughes passed away but his name has not been forgotten and he is remembered as a businessman/writer and pioneer of the mountains in the Forbidden Plateau.

In July 1928 Ben Hughes went in to Forbidden Plateau on an Alpine Club of Canada camp. Included on the trip was Claude Harrison, the president of the Vancouver Island section of the Alpine Club of Canada and Courtenay's Sid Williams. A party of twenty-eight climbed Mount Albert Edward and then the following day Hughes climbed Castle Mountain (Castlecrag) with eight others making the first ascent of this peak. Adrian Paul was amongst the party; however, he only climbed Mount Albert Edward. Both Ben Hughes and Adrian Paul then went on and climbed the Comox Glacier with Geoffrey Capes and two others in 1929; and in August 1930, Paul, along with David Guthrie and Henry Ellis, climbed Alexandra Peak for the first time as part of a four-day trip from Circlet Lake. While on Alexandra Peak they climbed The Thumb, a steep little rock tower that on two sides is either sheer or overhanging. Although these men undertook numerous other excursions into the mountains, the one that they are best remembered for is the trip into the Cliffe Glacier in July 1931 whereby they climbed The Red Pillar.

Their trip began by following the usual route up to Comox Lake and Forbush Lake but instead of climbing over Mount Evans (Kookjai Mountain), they continued up the Puntledge River to a river flowing down from the glaciers (Red Pillar Creek.) They fought their way through the Devil's Club and Slide Alder to a ridge that led up to the Cliffe Glacier and the mountain they called "The Pillar," which they hoped to climb. By lunch on the second day they had reached open ground near the toe of the Cliffe Glacier. "The Pillar" was close at hand, looking as formidable on close inspection as from the Comox Glacier.

Early Sunday morning the four attacked the reddish mass of rock via the North Face but this was soon found to be impregnable so they next sought a way up the steep West Face. A chimney was found that was difficult and in places blocked by chock stones but the climbers struggled with the rock, making every handhold count. After several hazardous moves the summit was finally gained and the climbers were able to relax. The summit was a large flat plateau with a snowfield of several acres. The only sign of life was a Ptarmigan and her famil, no doubt surprised and startled by the sight of these first humans. A rock cairn was built and a record left with a recommendation that the peak be called The Pillar.

It was a beautiful Vancouver Island summer day and the climbers lingered on the summit enjoying the spectacular views. To the west lay the mountains of Strathcona Park and in the valleys below lakes shimmered in the midday sun, beckoning the climbers down for a cool, refreshing swim.

It was time to leave the summit. The climb up the West face had been so difficult that a new route was attempted down the South Face. A route that was not quite so precipitous was found but it turned out to be more tedious. After descending, they traversed around the mountain and then crossed the Cliffe Glacier to the base of a mountain they called The Camel. They were hoping to find a way over this and onto the Comox Glacier but they found the climbing too dangerous. Initially they climbed over difficult scree slopes but a point was reached where they had to cross a thirty-foot wide snow slope. They were about five hundred feet above the glacier and on snow that they considered to be at an angle of sixty degrees. Without rope or ice axes, and with heavy packs, they made a decision to return the way they had come and reluctantly turned around and retraced their steps.

Once back in Courtenay the climbers suggested that the peak they failed on should be called The Camel. However, in 1934 when Norman Stewart, a British Columbia Land Surveyor, came to consult the local mountaineers about the nomenclature of the peaks and other prominent points in the area of Forbidden Plateau and Strathcona Park, he said there were numerous "Camel" mountains already in Canada. Stewart suggested that it should be called Ben Hughes Mountain but the proprietor of the Argus objected to this on the grounds that it was too personal, but agreed that it should be named after the paper he owned, and so it was. Stewart was also able to confirm that the Pillar Mountain be called The Red Pillar because of its characteristic colour and shape.

The second ascent of The Red Pillar occurred during the summer of 1934. William Moffat, a British Columbia Land Surveyor who emigrated from Ireland in 1912, was involved with the survey of the mountains with Norman Stewart, and while undertaking topographical surveys climbed the mountain before it was officially named The Red Pillar. Moffat suggested that it be called Mount Esther, the Christian name of an American woman who had been in the area of the glaciers that year with a party led by Harold Cliffe. This name did not receive much attention and was quickly dropped.

The

failure by Hughes, Leighton, Paul and Gregson on Argus

Mountain in 1931 led other mountaineers to believe that it

was harder to climb then The Red Pillar and it was many years before it

was attempted again. An article in the Comox Argus from July 6, 1949,

states that over the Dominion Day weekend, Argus

Mountain received its first ascent by Alex and William (Bill) Bell

of Courtenay. Bill was familiar with the glacial area, as he had undertaken

numerous trips into the region while working for the surveyors in the

1930's. The Bell Brothers took the usual route into the Comox Glacier

and camped on a rock ledge between the glacier and Argus Mountain. On

July 2, they climbed a long, steep gully that took them to a col between

the two summits. The ascent was easier then they had anticipated but they

used the rope to be safe as a fall could be fatal. The brothers returned

triumphant having believed they had climbed the last unclimbed mountain

around the two glaciers. However, this may not be quite true.

The

failure by Hughes, Leighton, Paul and Gregson on Argus

Mountain in 1931 led other mountaineers to believe that it

was harder to climb then The Red Pillar and it was many years before it

was attempted again. An article in the Comox Argus from July 6, 1949,

states that over the Dominion Day weekend, Argus

Mountain received its first ascent by Alex and William (Bill) Bell

of Courtenay. Bill was familiar with the glacial area, as he had undertaken

numerous trips into the region while working for the surveyors in the

1930's. The Bell Brothers took the usual route into the Comox Glacier

and camped on a rock ledge between the glacier and Argus Mountain. On

July 2, they climbed a long, steep gully that took them to a col between

the two summits. The ascent was easier then they had anticipated but they

used the rope to be safe as a fall could be fatal. The brothers returned

triumphant having believed they had climbed the last unclimbed mountain

around the two glaciers. However, this may not be quite true.

Nowadays, Argus Mountain can be climbed as a long day trip, by fit climbers,

from a camp at the Frog Ponds east of Blackcat Mountain; however, ascents

are made easier in the spring/early summer before moats form at the bottom

of the steep snow gully. The Red Pillar and Mount Harmston are different

propositions because of their location, and usually require more time.

Although the two glaciers are not difficult, it is important to have a

rope and for the climbers to be proficient in its use. Crevasses can remain

hidden by last season's snow cover or freshly fallen snow, and as has

been seen around the world, they can be a deadly for both the uninitiated

and the experienced. The local glaciers are no exceptions. However, the

effort required by mountaineers to get to the Cliffe Glacier and the surrounding

mountains is worth the toil when one sees the incredible views of both

the Comox and Alberni Valleys, and the mountains of Strathcona Park.

How to order | | About the Author || Links || Home

Contact:

Copyright ©

Lindsay Elms 2001. All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.beyondnootka.com

http://www.lindsayelms.ca