Island Stories:

![]() Danzig

Mine

Danzig

Mine

![]() Zeballos

Iron Mine

Zeballos

Iron Mine

![]() Conuma

Peak 1910

Conuma

Peak 1910

Alexandra Peak

Argus Mountain

Bate/Alava Sanctuary

Beaufort Range

Big Interior Mtn

Big Interior Mtn 1913

Part 1

Part 2

Bolton Expedition 1896

Cliffe Glacier

Clinton Wood

Comox Glacier

Comox Glacier 1922

Comox Glacier 1925

Comstock Mtn

Conuma Peak

Copper King Mine

Crown Mtn

Elkhorn 1912

Elkhorn 1949

Elkhorn 1968

Eugene Croteau

Golden Bullets

Golden Hinde 1913/14

Golden Hinde 1937

Golden Hinde 1983

Harry Winstone Tragedy

Jack Mitchell

Jim Mitchell Tragedy

John Buttle

Judges Route

Koksilah's Silver Mine

Landslide Lake

Mackenzie Range

Malaspina Peak

Mariner Mtn

Marjories Load

Matchlee Mountain

Mount McQuillan

Mt. Albert Edward

Mt. Albert Edward 1927

Mt. Albert Edward 1938

Mt. Becher

Mt. Benson 1913

Mt. Benson

Mt. Doogie Dowler

Mt. Colonel Foster

Mt. Hayes/Thistle Claim

Mt. Maxwell

Mt. Sicker

Mt. Tzouhalem

Mt. Whymper

Muqin/Brooks Peninsula

Nine Peaks

Queneesh

Ralph Rosseau 1947

Rosseau Chalet

Ralph Rosseau Tragedy

Rambler Peak

Red Pillar

Rex Gibson Tragedy

Sid's Cabin

Steamboat Mtn

Strathcona Park 1980's

The Misthorns

The Unwild Side

Victoria Peak

Waterloo Mountain 1865

Wheaton Hut/Marble Meadows

William DeVoe

Woss Lake

You Creek Mine

Zeballos Peak

Other Stories:

Sierra

de los Tuxtlas

Antarctica

Cerro del Tepozteco

Citlaltepetl

Huascaran

Mt. Roraima

Nevada Alpamayo

Nevada del Tolima

Nevado de Toluca

Pico Bolivar

Popocatepetl

Uluru/Ayers Rock

Volcan Purace

Volcan San Jose

Biographies

Island 6000

Cartoons

Order the Book

Contact Me

Links

Clinton

Wood:

The

Dove Creek Trail and Forbidden Plateau Lodge

by Lindsay Elms

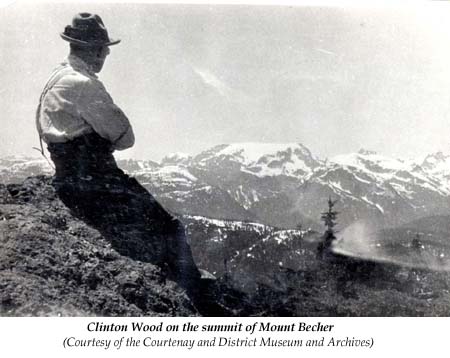

On

July 6, 1926, Clinton Stuart Wood, in the company of Cecil

(Cougar) Smith and two saddle horses, set out on their first

trip to Mount Albert Edward via the trail from Bevan, up to Mount Becher

and on to the plateau. On the second day they reached a small log cabin

built by John

(Nigger) Brown near Circle (Circlet) Lake but chose

to sleep outside due to a "belligerent family of wasps" who

had taken over the cabin. Here they tethered the horses on a long rope

while the next day they climbed to the summit. There they found a rock

cairn and assumed it had been erected by the surveyors who had worked

on the eastern boundary of Strathcona Park. After descending back to the

cabin they then headed down to Divers Lake and then returned up the draw

between Strata Mountain and Limestone Ridge (Mount Allan Brooks) to Goose

(Mackenzie) Lake. East of the lake they climbed another mountain (Mount

Drabble) to get a view of the surrounding terrain. Wood was so impressed

with the sub-alpine scenery of the plateau that the next year he returned

with Claude

Harrison, president of the Vancouver Island section of the

Alpine Club of Canada, and again climbed Mount

Albert Edward. However, this time the weather wasn't quite

as amenable as the fog came in while they were on the summit but Wood's

knowledge of the terrain and good sense of direction won through and they

got back safely to their camp. The result of this successful trip was

a joint Alpine Club and Courtenay-Comox Mountaineering Club (CDMC) camp

held in the summer of 1928 on the Forbidden Plateau. This time Claude

Harrison had the views he had missed out on during his first visit. He

was so impressed with the beauty and scope of mountains on the Forbidden

Plateau that he presented slides shows in Victoria in which a great deal

of favourable publicity resulted.

On

July 6, 1926, Clinton Stuart Wood, in the company of Cecil

(Cougar) Smith and two saddle horses, set out on their first

trip to Mount Albert Edward via the trail from Bevan, up to Mount Becher

and on to the plateau. On the second day they reached a small log cabin

built by John

(Nigger) Brown near Circle (Circlet) Lake but chose

to sleep outside due to a "belligerent family of wasps" who

had taken over the cabin. Here they tethered the horses on a long rope

while the next day they climbed to the summit. There they found a rock

cairn and assumed it had been erected by the surveyors who had worked

on the eastern boundary of Strathcona Park. After descending back to the

cabin they then headed down to Divers Lake and then returned up the draw

between Strata Mountain and Limestone Ridge (Mount Allan Brooks) to Goose

(Mackenzie) Lake. East of the lake they climbed another mountain (Mount

Drabble) to get a view of the surrounding terrain. Wood was so impressed

with the sub-alpine scenery of the plateau that the next year he returned

with Claude

Harrison, president of the Vancouver Island section of the

Alpine Club of Canada, and again climbed Mount

Albert Edward. However, this time the weather wasn't quite

as amenable as the fog came in while they were on the summit but Wood's

knowledge of the terrain and good sense of direction won through and they

got back safely to their camp. The result of this successful trip was

a joint Alpine Club and Courtenay-Comox Mountaineering Club (CDMC) camp

held in the summer of 1928 on the Forbidden Plateau. This time Claude

Harrison had the views he had missed out on during his first visit. He

was so impressed with the beauty and scope of mountains on the Forbidden

Plateau that he presented slides shows in Victoria in which a great deal

of favourable publicity resulted.

It was the difficulties of the trail via Bevan and Mount Becher and the time that it usually took most parties to get to the plateau that led Clinton Wood in the search to locate an easier route to the plateau. Dove Creek just to the south of Mount Washington looked the most promising access so with Geoffrey Capes, a Courtenay mountaineer, they decided to investigate it. This route appeared the most logical to Wood.

In The Islander from Sunday, January 21, 1968, a supplement of the Victoria Daily Colonist newspaper, Clinton Wood wrote:

We started one afternoon from the point where the creek crossed an old diamond drill road, with our packs full of supplies for a week. We followed the bed of the creek, and very interesting it was, in places as smooth as a cement road and bordered on each side by sheer rock walls with many seams of coal outcropping.

There were times when the going got very difficult and we were forced to leave the bed of the creek and make our way through the thick jungle bordering each bank.

We kept on till darkness forced us to stop. We were now in the bed of the creek, but as the water was low we were able to find a convenient sandbar upon which to spread our blankets. The weather was fine and with a good fire to keep us warm, we spent a quite comfortable night.

By daylight, with our blankets and grub on our backs and the fire blackened, billy-can dangling in the rear, we were again on our way.

By 9 A.M. Anderson Lake, the source of Dove Creek, was reached. Two very beautiful fantastically contoured falls were observed en route and a very difficult traverse had to be made.

After leaving Anderson Lake we were in unknown country, with not a blaze on a tree, nor any evidence of having ever been visited by any human being.

We left the lake at 10 A.M. and headed up the mountain to the south. About noon we came to what appeared to be the height of land and from all appearances easier traveling, …Our hopes were short lived as, without warning, heavy clouds started drifting in, the wind began to blow and soon all the bushes were saturated, and so were we. This was bad because we were now unable to pick up any landmarks to chart our route and had to depend on our compasses …

It was true that with the help of our compasses, it was possible to make sure that we were moving in the correct general direction, which in this instance was south. If we continued on our course, we must eventually come to the trail from Mt. Becher to Mt. Albert Edward.

By 8 P.M. that night they had still not reached there objective but with a small candle lit by a hand that was shaking with cold from the rain that had set in that afternoon they eventually managed to get a good fire burning. The next morning the sun came out and an hour later they found the old trail.

As a result of this trip Wood realized that a route via Dove Creek was feasible. A number of other scouting trips were necessary to locate and properly blaze a trail but with the backing of the local mountaineering club (CDMC) and the Courtenay and Comox Board of Trade Wood was able to secure provincial funding to work on the trail.

On July 18, 1929 the Dove Creek Trail was officially opened by the Honorable Randolph Bruce, the Lieutenant-Governor to the province and a number of local dignitaries attended including Courtenay's Mayor Theed Pearse and his wife Elma, MLA Doctor George McNaughton a medical doctor from Cumberland, Clinton Wood the President of the Comox District Mountaineering Club, and Miss Helen McKenzie a niece of Randolph Bruce.

On July 25, 1929 the headlines of the Comox Argus newspaper read "Forbidden Plateau now Bidden Plateau" with the subtitle "Lieutenant-Governor Opens new Dove Creek Trail …" On the day of opening Clinton Wood remarked:

[T]he trail would bring within a half day's travel, a new Switzerland, full of beautiful lakes and meadows, where the people who lived on the coast could get to higher altitudes. As to mountaineering many of the peaks that could be reached by this trail had never been named or climbed and there were many beautiful lakes that had yet to be named. Hunters would see deer in the alpine meadow quite fearless of man, and naturalists would revel in a wealth of alpine flora.

Doctor George McNaughton also spoke on the future of the trail: "It was the beginning of an advertising campaign for the Comox District which, they trust, would bring in many tourists to enjoy the many beauties of this part of the island." Finally, upon opening the trail the Honorable Randolph Bruce added his thoughts that bolstered what Wood and McNaughton had said:

In the future the Forbidden Plateau would be the Bidden Plateau and all the sons of Adam and daughters of Eve will want to go into this country which has been so long denied them. It would be a source of joy and inspiration to the army of tourists that were coming into Canada and leaving 220 million dollars behind them, an amount equal to the value of what exported out of the country.

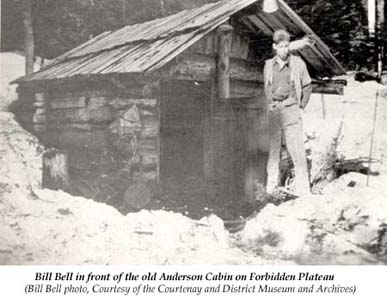

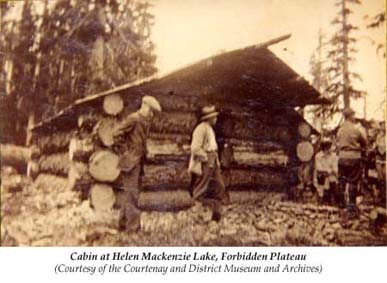

In June, 1930 Bruce Towler was placed in-charge of a crew that included Jack Hames and William (Bill) Bell who worked on the Dove Creek Trail pushing it as far as Lake Helen Mackenzie. Hames became well known for his newspaper writings and book Field Notes: An Environmental History while Bell, an avid hiker/mountaineer, packed for Norman Stewart who was in-charge of the topographical survey of Strathcona Provincial Park in the mid 1930's and then worked in the logging industry. Later he became a Courtenay Alderman. Clinton Wood believed that this trail would be an important contribution toward the development of establishing a major tourist attraction for Vancouver Island.

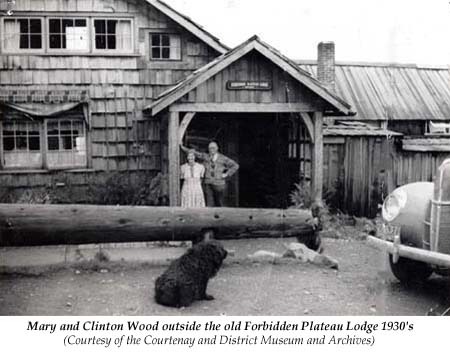

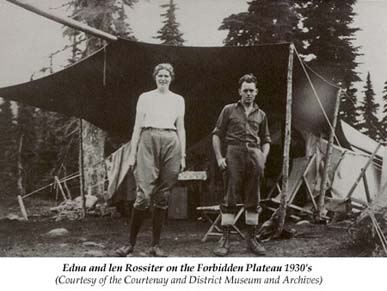

In

1934 Clinton Wood built the Forbidden Plateau Lodge as a guest lodge that

he and his wife Mary operated for eleven years before retiring. The lodge

consisted of four cabins, two outhouses, the main building and a barn

that unfortunately burnt down just after completion. They also erected

a tent at McKenzie Lake as an intermediate camp. After establishing the

Plateau Lodge, Clinton and his son Stuart operated a packhorse team for

mountaineers and tourists via the Mount

Becher Trail. Cabins were built at Mackenzie Lake and Mariwood

Lake (named after Clinton's wife Mary) and for many years' guides who

lived at the camps for the summer led tourists up the surrounding mountains

and to the various stocked lakes fishing. Over the years Wood's used locals

as guides that included Jack

Mitchell, Bob Gibson, George Maclean and Len Rossiter. Rossiter

spent many years exploring the plateau and surrounding mountains and has

a lake named in his honour.

In

1934 Clinton Wood built the Forbidden Plateau Lodge as a guest lodge that

he and his wife Mary operated for eleven years before retiring. The lodge

consisted of four cabins, two outhouses, the main building and a barn

that unfortunately burnt down just after completion. They also erected

a tent at McKenzie Lake as an intermediate camp. After establishing the

Plateau Lodge, Clinton and his son Stuart operated a packhorse team for

mountaineers and tourists via the Mount

Becher Trail. Cabins were built at Mackenzie Lake and Mariwood

Lake (named after Clinton's wife Mary) and for many years' guides who

lived at the camps for the summer led tourists up the surrounding mountains

and to the various stocked lakes fishing. Over the years Wood's used locals

as guides that included Jack

Mitchell, Bob Gibson, George Maclean and Len Rossiter. Rossiter

spent many years exploring the plateau and surrounding mountains and has

a lake named in his honour.

Clinton Wood's reward for the time and energy he put into the Forbidden Plateau was to see it finally acquired and designated a Class A provincial park in 1962. Len Rossiter was delighted in 2000 when the NDP Government announced Rossiter and Diver's Lake were to also be added to the park although it wasn't until 2003 that it got official status. Both fitting tributes to the dedication of the two men whose lives are forever linked to Forbidden Plateau.

|

|

|

|

How to order | | About the Author || Links || Home

Contact:

Copyright ©

Lindsay Elms 2001. All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.beyondnootka.com

http://www.lindsayelms.ca