Island Stories:

![]() Danzig

Mine

Danzig

Mine

![]() Zeballos

Iron Mine

Zeballos

Iron Mine

![]() Conuma

Peak 1910

Conuma

Peak 1910

Alexandra Peak

Argus Mountain

Bate/Alava Sanctuary

Beaufort Range

Big Interior Mtn

Big Interior Mtn 1913

Part 1

Part 2

Bolton Expedition 1896

Cliffe Glacier

Clinton Wood

Comox Glacier

Comox Glacier 1922

Comox Glacier 1925

Comstock Mtn

Conuma Peak

Copper King Mine

Crown Mtn

Elkhorn 1912

Elkhorn 1949

Elkhorn 1968

Eugene Croteau

Golden Bullets

Golden Hinde 1913/14

Golden Hinde 1937

Golden Hinde 1983

Harry Winstone Tragedy

Jack Mitchell

Jim Mitchell Tragedy

John Buttle

Judges Route

Koksilah's Silver Mine

Landslide Lake

Mackenzie Range

Malaspina Peak

Mariner Mtn

Marjories Load

Matchlee Mountain

Mount McQuillan

Mt. Albert Edward

Mt. Albert Edward 1927

Mt. Albert Edward 1938

Mt. Becher

Mt. Benson 1913

Mt. Benson

Mt. Doogie Dowler

Mt. Colonel Foster

Mt. Hayes/Thistle Claim

Mt. Maxwell

Mt. Sicker

Mt. Tzouhalem

Mt. Whymper

Muqin/Brooks Peninsula

Nine Peaks

Queneesh

Ralph Rosseau 1947

Rosseau Chalet

Ralph Rosseau Tragedy

Rambler Peak

Red Pillar

Rex Gibson Tragedy

Sid's Cabin

Steamboat Mtn

Strathcona Park 1980's

The Misthorns

The Unwild Side

Victoria Peak

Waterloo Mountain 1865

Wheaton Hut/Marble Meadows

William DeVoe

Woss Lake

You Creek Mine

Zeballos Peak

Other Stories:

Sierra

de los Tuxtlas

Antarctica

Cerro del Tepozteco

Citlaltepetl

Huascaran

Mt. Roraima

Nevada Alpamayo

Nevada del Tolima

Nevado de Toluca

Pico Bolivar

Popocatepetl

Uluru/Ayers Rock

Volcan Purace

Volcan San Jose

Biographies

Island 6000

Cartoons

Order the Book

Contact Me

Links

Mount

Roraima:

An

Island Forgotten by Time

by Lindsay Elms

Deep within the heart of Venezuela's dark and mysterious jungle lie islands; not islands that have coconut laden palm trees swaying in the warm summer breeze or crystaline blue water lapping backwards and forwards onto white sandy beaches, but isolated islands of sandstone forgotten by time.

To the Pemon, the indigenous people of the region known as the Gran Sabana, these flat-topped mountains or mesas are called tepuis. Most of these tepuis are remote and are almost permanently shrouded in mist and clouds, even during the dry season. Thunderstorms are frequent and torrential downpours are a way of life. Some of the tepuis have swamp-like surfaces while others have been washed by rainfall to almost sheer sandstone.

Geologists

have conducted chronological-dating tests on molten rock that has thrust

its way up between layers of sandstone after these ancient plateaus were

formed. The dates they came up with were astounding: The sandstone is

estimated to be at least 1.8 billion years old. It is because of the tepuis

isolation and old age that have made them special. Each tepuis flora and

fauna has been found to be unique. Many species of lichens, mosses, orchids

and insects are found nowhere else and have adapted themselves to their

harsh environments on the mountaintops.

Geologists

have conducted chronological-dating tests on molten rock that has thrust

its way up between layers of sandstone after these ancient plateaus were

formed. The dates they came up with were astounding: The sandstone is

estimated to be at least 1.8 billion years old. It is because of the tepuis

isolation and old age that have made them special. Each tepuis flora and

fauna has been found to be unique. Many species of lichens, mosses, orchids

and insects are found nowhere else and have adapted themselves to their

harsh environments on the mountaintops.

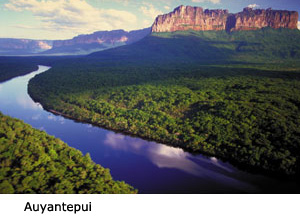

Although

Mount Roraima (2,772m) is the most famous Tepui, there are several others

that are of special interest. Salto Angel, or Angel Falls, the highest

waterfall in the world, exits from the summit of Auyan-tepui (2,460m)

a 435 square mile heart shaped table mountain in the southeastern Gran

Sabana. In October 1937 an American bush pilot, Jimmie Angel, landed his

plane, the El Rio Caroni, on the summit while in search of the lost river

of gold. Angel had flow over the Tepui in 1933 and into Devil's Canyon

and discovered what he called "a mile high waterfall," later

to be named after him. At first, Angel's Auyan-tepui landing appeared

to be perfect, but the wheels broke through the sod and sank into the

mud bringing the airplane to an abrupt halt with a broken fuel line and

the airplane's nose buried in the mud. With the plane hopelessly mired

in her muddy landing spot the landing party started the long march from

the mountain to the village of Kamarata in the valley below.

Although

Mount Roraima (2,772m) is the most famous Tepui, there are several others

that are of special interest. Salto Angel, or Angel Falls, the highest

waterfall in the world, exits from the summit of Auyan-tepui (2,460m)

a 435 square mile heart shaped table mountain in the southeastern Gran

Sabana. In October 1937 an American bush pilot, Jimmie Angel, landed his

plane, the El Rio Caroni, on the summit while in search of the lost river

of gold. Angel had flow over the Tepui in 1933 and into Devil's Canyon

and discovered what he called "a mile high waterfall," later

to be named after him. At first, Angel's Auyan-tepui landing appeared

to be perfect, but the wheels broke through the sod and sank into the

mud bringing the airplane to an abrupt halt with a broken fuel line and

the airplane's nose buried in the mud. With the plane hopelessly mired

in her muddy landing spot the landing party started the long march from

the mountain to the village of Kamarata in the valley below.

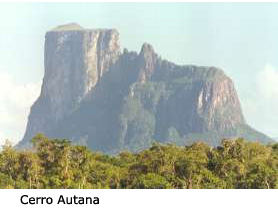

To

the south of Puerto Ayacucho, a city on the outskirts of the Orinoco jungle

near Colombia, is Cerro Autana. This is a sacred mountain of the Piaroa

Indians who believe it is the trunk of the tree bearing the fruits and

seeds of the land. This Tepui is only 1220m high but has a labyrinth of

caves near the summit which at certain times of the year, the sun's rays

shine in on one side of the mountain and out the other. Nearby is Cerro

Pintado or the Painted Mountain, which has the largest petroglyphs in

Venezuela, including a fifty metre snake that is said to represent the

Orinoco River.

To

the south of Puerto Ayacucho, a city on the outskirts of the Orinoco jungle

near Colombia, is Cerro Autana. This is a sacred mountain of the Piaroa

Indians who believe it is the trunk of the tree bearing the fruits and

seeds of the land. This Tepui is only 1220m high but has a labyrinth of

caves near the summit which at certain times of the year, the sun's rays

shine in on one side of the mountain and out the other. Nearby is Cerro

Pintado or the Painted Mountain, which has the largest petroglyphs in

Venezuela, including a fifty metre snake that is said to represent the

Orinoco River.

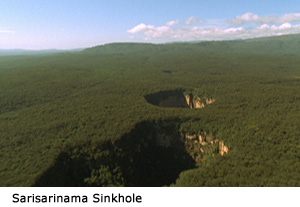

Even

further to the south in the remote Amazonas region is the Sierra de la

Neblina (Mountains of the Mists). This range is so remote that the highest

mountain, Pico da Neblina (3014m), was not discovered until 1953 and then

it was another twelve years (1965) before it received its first ascent.

Another fascinating tepui is Cerro Sarisarinama with huge sink-holes on

its forested summit. These perfectly circular sinkholes or "simas"

vary in size with the largest being 350 metres deep by 350 metres in diameter.

To the Ye'kuana Indians who live nearby the name of this tepui comes from

the sound (Sari….Sari….) made by the Evil Spirit who lives atop

the mountain when he eats human beings.

Even

further to the south in the remote Amazonas region is the Sierra de la

Neblina (Mountains of the Mists). This range is so remote that the highest

mountain, Pico da Neblina (3014m), was not discovered until 1953 and then

it was another twelve years (1965) before it received its first ascent.

Another fascinating tepui is Cerro Sarisarinama with huge sink-holes on

its forested summit. These perfectly circular sinkholes or "simas"

vary in size with the largest being 350 metres deep by 350 metres in diameter.

To the Ye'kuana Indians who live nearby the name of this tepui comes from

the sound (Sari….Sari….) made by the Evil Spirit who lives atop

the mountain when he eats human beings.

Mount

Roraima was made famous in 1912 when Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle wrote his

fictional novel entitled The Lost World. It describes the ascent

of a Roraima-like mountain by an exploratory party in search of prehistoric

plants and dinosaurs that were believed to live isolated and unchanged

for millions of years on the mountains summit. Conan-Doyle was inspired

by the British botanist Everard Im Thurn who on December 18, 1884 with

Harry Perkins, was the first to reach the summit of Mount Roraima. Im

Thurn and Perkins were not the first Europeans to see Mount Roraima, that

goes to Robert Schomburgk, a German born explorer and scientist who explored

the region for Britains's Royal Geographical Society in 1838. When Im

Thurn returned to Europe to present lectures on his expedition, Conan-Doyle

attended one of his shows and was fascinated by the account, allowing

his fervent imagination to wander.

Mount

Roraima was made famous in 1912 when Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle wrote his

fictional novel entitled The Lost World. It describes the ascent

of a Roraima-like mountain by an exploratory party in search of prehistoric

plants and dinosaurs that were believed to live isolated and unchanged

for millions of years on the mountains summit. Conan-Doyle was inspired

by the British botanist Everard Im Thurn who on December 18, 1884 with

Harry Perkins, was the first to reach the summit of Mount Roraima. Im

Thurn and Perkins were not the first Europeans to see Mount Roraima, that

goes to Robert Schomburgk, a German born explorer and scientist who explored

the region for Britains's Royal Geographical Society in 1838. When Im

Thurn returned to Europe to present lectures on his expedition, Conan-Doyle

attended one of his shows and was fascinated by the account, allowing

his fervent imagination to wander.

Im Thurn

climbed Mount Roraima from the southeast by what is now called the Im

Thurn route, the only easy way to the summit. His expedition had to fight

their way through hundreds of miles of wild rivers and jungles, confronting

dangerous animals and savage Indians. Eventually he was within striking

distance of the summit:

Up to this part of the slope our ascent had been fairly easy. We have now reached a spot where one long climb will take us to the level summit, and we shall behold that which has never been observed since the beginning of the world. Although we can't say that the entire world has been waiting to see what our eyes will now behold, at least quite a few people have been anxious to know. We shall see that which the few white or copper-coloured people who have viewed the mountain declared would remain unknown as long as the world existed. We shall know what is Roraima.

After Im Thurn and Perkins, other British scientific expeditions arrived to collect and classify the strange flora and fauna found on the mountain: F.V. McConnell and J.J. Quelch in 1894 and 1898, three expeditions of the Boundary Commission in 1900, 1905 and 1910, Koch Grumberg in 1911, C. Clementi in 1916 and G.H. Tate of the New York Museum of Natural History in 1917. Four more expeditions visited the mountain in the next sixty years and then the noted Venezuelan naturalist/explorer Charles Brewer-Carias became interested in the tepuis. Brewer-Carias made repeated scientific journeys into the tepuis discovering and collecting many new species.

Mount Roraima has been studied by botanists, zoologists, geologists, herpetologists, orchidologists, ecologists, limnologists, entomologists, edaphologists and many more whose names don't mean much to mountaineers but are important to science. It is their information that sparks others interests in these bizzare formations.

It was Im

Thurns accounts that also attracted British mountaineers Hamish MacInnes,

Joe Brown, Don Whillans and Mo Anthonie to Mount Roraima in 1967. They

wanted to climb the mountain by a new route and chose 'the prow' located

at the northern end of the plateau that juts into Guyana. MacInnes's account

can be read in his book Climb to the Lost World.

It was the these stories of prehistoric plants and dinosaurs, bizarre labyrinths, adventure, and a chance to go back in time that saw Elaine Kerr, Wytze Visser and myself hiking into Mount Roraima in March 1994.

From Caracas we spent three long, hot days driving to the town of San Francisco de Yuruani near the border of Brazil. This town is the jump-off point for Mount Roraima. Basic services were available and there were many hawkers trying to sell Indian blowpipes, bows and arrows and the usual tourist trinkets. Of interest to us was the guide service that provided jeeps to take us in the twenty-five kilometres to Paraitepuy. It was possibly to save the $25 and walk but that would waste another day and we were anxious to get to the mountain.

Paraitepuy is a dusty, dirty little town where the inhabitants eke out a living guiding people into Roraima. The jeep dropped us off at the Imparque office (National Parks) where a Ranger came out and asked us to come into his office. In Spanish he explained to us that we couldn't go into the mountain without a guide at $25/day and if we needed a porter that was $30/day. It was hard to justify the cost of a guide when we could see Mount Roraima and the trail leading all the way to its base. Arrangements were made to hire a guide for five days as this was how long we expected it to take us to get into the mountain, climb it and get out. We had to pay the Ranger half of the cost up front, which he would give to the guide, and then we would pay the remainder to the guide at the end of the trip. As it was mid afternoon we didn't want to wait around until the following morning so we agreed for the guide to meet us next day about two hours down the trail.

At

5:20am we were awoken by the sound of footsteps approaching our tent.

It was our guide who had decided to get to us early as he was concerned

we would take off without him. Epifanio Ayuso Sucre had been guiding for

twenty years and was one of the original guides, having been born at the

base of Roraima. His family and many others, moved to Paraitepuy from

outlying hamlets when electricity was introduced to the village. Half

an hour later we were walking in the cool of the morning hoping to get

as much distance behind us before the heat of the afternoon became too

much.

At

5:20am we were awoken by the sound of footsteps approaching our tent.

It was our guide who had decided to get to us early as he was concerned

we would take off without him. Epifanio Ayuso Sucre had been guiding for

twenty years and was one of the original guides, having been born at the

base of Roraima. His family and many others, moved to Paraitepuy from

outlying hamlets when electricity was introduced to the village. Half

an hour later we were walking in the cool of the morning hoping to get

as much distance behind us before the heat of the afternoon became too

much.

The trail followed rolling ridges through the fire-scorched savannah to the Rio Kukenan, the last major river. Most parties stop here for the first night but it was only mid morning so we continued on for another couple of hours. The afternoon was spent snoozing under a large rock and then when it began to cool down we moved on to Campamento Abajo (base camp) at the bottom of Mount Roraima's imposing wall.

Base camp was at around 2000m and was high enough to see over the surrounding savannah and the many grass fires burning. At dusk the fireflies or 'insectos de bomberos' (firemen insects) as Epifanio called them, came out and put on a display. Epifanio was a Pemon Indian and his first language was Pemon so his Spanish was as limited as ours but his love for the area was infectious and we were able to communicate with each other.

The climb

up to the summit plateau took about four hours and passed through thick,

lush vegetation, an area with a refreshing smell of life and a pungent

odour of decay mixed together. As we ascended we followed a ramp up through

the wall that offered the only line of resistance. This was the route

that Im Thurn took over one hundred years ago. To our right the coloured

sandstone wall loomed up sheer for five hundred metres while the trail

in places was less than a metre wide.  Half

way up the trail descended for fifty metres to get around a airy rock

buttress and then we had a cold shower as we passed under a cascading

waterfall before scrambling up a rocky gully that finally brought us onto

the summit plateau. The summit was shrouded in mist and we soon found

the benefit of having Epifanio with us. In places we were able to pick

out a trail worn by feet on the sandstone, but generally there was no

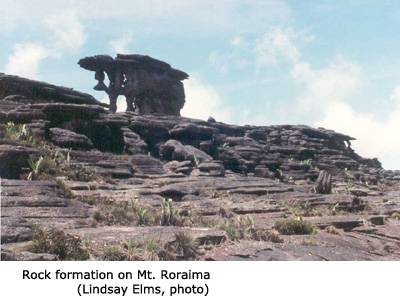

sign. Straight away we began seeing numerous bizarre rock formations.

Huge rocks balanced on what looked like fragile columns. Obviously not

as fragile as they look as they've been supporting this weight for millions

of years. Epifanio guided us to one of the two dry campsites where you

could camp without having to worry about being flooded by the afternoon

downpours.

Half

way up the trail descended for fifty metres to get around a airy rock

buttress and then we had a cold shower as we passed under a cascading

waterfall before scrambling up a rocky gully that finally brought us onto

the summit plateau. The summit was shrouded in mist and we soon found

the benefit of having Epifanio with us. In places we were able to pick

out a trail worn by feet on the sandstone, but generally there was no

sign. Straight away we began seeing numerous bizarre rock formations.

Huge rocks balanced on what looked like fragile columns. Obviously not

as fragile as they look as they've been supporting this weight for millions

of years. Epifanio guided us to one of the two dry campsites where you

could camp without having to worry about being flooded by the afternoon

downpours.

As we wondered around we had the feeling we were in an alien environment. At every turn we expected to meet some prehistoric creature or the 'missing link' but all we met were the carnivores Heliaphora nutans or giant pitcher plants. These plants capture insects to obtain nitrogen and other nutrients that are absent on the sandstone formations.

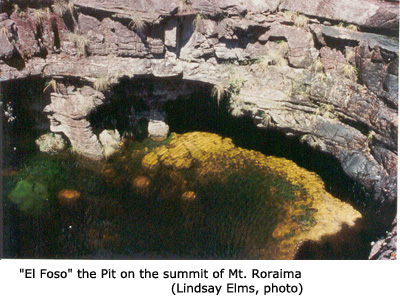

The

next morning dawned clear but we had a cold wind blowing. We started out

to visit a geographic landmark called Punto Tres. This is where Venezuela,

Guyana and Brazil meet, a place about eight kilometres away from camp

but less the halfway across the summit plateau. It would be virtually

impossible to find this place on your own due to the topography so were

glad to have Epifanio along. Along the way we entered the beautiful little

canyon of the Arabopo River. It felt like a place straight out of a fairy

tale. Not far away was El Foso or 'the pit', a deep, dark cavern with

a running stream. This stream disappeared underground and then reappeared

emerging as a cascade from Mount Roraima's outer wall.

The

next morning dawned clear but we had a cold wind blowing. We started out

to visit a geographic landmark called Punto Tres. This is where Venezuela,

Guyana and Brazil meet, a place about eight kilometres away from camp

but less the halfway across the summit plateau. It would be virtually

impossible to find this place on your own due to the topography so were

glad to have Epifanio along. Along the way we entered the beautiful little

canyon of the Arabopo River. It felt like a place straight out of a fairy

tale. Not far away was El Foso or 'the pit', a deep, dark cavern with

a running stream. This stream disappeared underground and then reappeared

emerging as a cascade from Mount Roraima's outer wall.

At Punto Tres there was a large cement cairn. Walking around it visiting three countries in as many steps was reminiscent of walking around the barber pole at the South Pole. Twenty minutes beyond Punto Tres we entered another little canyon, a tributary of the Arabopo River called Valle de los Cristales - 'valley of the crystals'. Beneath our feet the ground sparkled with pink and white quartz crystals. In places scattered around were large fragments of the quartz, obviously removed from the creekbed by crystal hunters looking for souvenirs. Many of the crystals have been crushed by people walking over them and in time there will be very little left unless some form of protection is implemented.

We wandered slowly back to camp passing Piedra Del Mono (monkey rock) and Dolphina, and through a mini labyrinth where our echoes reverberated off every rock making it impossible to find anybody even if they were only a few metres away.

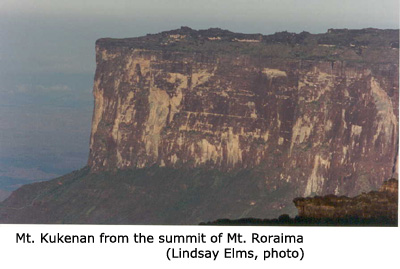

That evening we watched a beautiful sunset over the neighbouring Mount Kukenan, and further to the south over the Amazon jungle forked lightning illuminated the night sky late into the evening. Birds soared on the thermals and up-thrusts created by the mountain's vertical walls and the sounds of the jungle echoed in our ears.

It

was time to head down the mountain and back to Paraitepuy. We were not

disappointed with Mount Roraima, we had stepped back into time to a place

where the earth had begun. A place where time had stood still and remained

unchanged for millions of years. We left wanting more, to see what was

on the summit of the next Tepui and the one after that; we had caught

Tepui fever.

It

was time to head down the mountain and back to Paraitepuy. We were not

disappointed with Mount Roraima, we had stepped back into time to a place

where the earth had begun. A place where time had stood still and remained

unchanged for millions of years. We left wanting more, to see what was

on the summit of the next Tepui and the one after that; we had caught

Tepui fever.

How to order | | About the Author || Links || Home

Contact:

Copyright ©

Lindsay Elms 2001. All Rights Reserved.

URL: http://www.beyondnootka.com

http://www.lindsayelms.ca